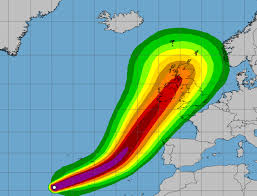

Our recent brush with the formidable Hurricane Ophelia and then a week later with the more colloquial sounding storm “Brian”, may have shaken our thinking that nothing very seriously bad ever happens in little ol’ Ireland.

Our recent brush with the formidable Hurricane Ophelia and then a week later with the more colloquial sounding storm “Brian”, may have shaken our thinking that nothing very seriously bad ever happens in little ol’ Ireland.

We are used to watching TV footage of storm-ravaged homes and people whose lives have been turned upside down in areas we typically associate with hurricanes, earthquakes and other natural disasters. But maybe now we can feel a little more empathy towards those situations and realise that natural disasters are perhaps something we should give a little more thought to in this part of the world.

Our WeMakeDo family philosophy has at times swung from the milder form of doing what we can to limit our harmful impact on the world to sometimes more extreme thoughts of how would we fare in the event of an extreme disaster where some degree of self-sufficiency may become very important.

The Normalcy Bias – sometimes also called the ostrich effect – is an effect that biases people’s thinking when faced with the prospect of disaster. We all tend to have this bias to varying degrees which dictates that things will continue to be normal because they have always been normal. This bias can come into play when we face a potential disaster situation and try to plan accordingly. The bias will tend to make us think things will never be as bad for us as we know it can be for others.

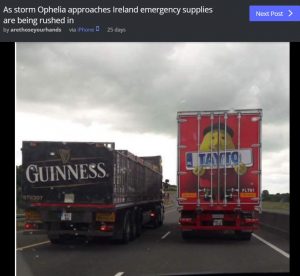

In true Irish fashion, before Ophelia struck, there were jokes going around about how Guinne ss and Taytos were all that was needed to weather it out. Maybe we just are that relaxed about things but perhaps there was some Normalcy Bias at play. It can result in way over-optimistic interpretations of warnings as well as an inability to cope well when faced with real disaster situations when they do occur.

ss and Taytos were all that was needed to weather it out. Maybe we just are that relaxed about things but perhaps there was some Normalcy Bias at play. It can result in way over-optimistic interpretations of warnings as well as an inability to cope well when faced with real disaster situations when they do occur.

Ophelia has been a striking example of why we should acknowledge that this kind of event can happen here. We should not assume we won’t experience disaster just because we have never really experienced it in recent memory.

Watching the aftermath of the storm unfold was interesting. It would seem that other than some specific tragic incidents during the storm, the broader population was merely inconvenienced by this storm. Our family like so many others lost our power, but only for a day and our water supply for the same time (as we are on a well). Others around us lost their power for a week and daily life for those families was certainly tough for those few days. What was eye-opening is how truly helpless we can be when we lose centrally supplied power or centrally supplied water. The loss of internet access in our home for a day was difficult enough!

Power was slowly restored and roof tiles were replaced and life went on for those of us less impacted by the storm. But should we give a little more thought to how well set up our current way of life is for dealing with large-scale disaster?

Power was slowly restored and roof tiles were replaced and life went on for those of us less impacted by the storm. But should we give a little more thought to how well set up our current way of life is for dealing with large-scale disaster?

It’s not so much that we should expect to have to deal with large storms like this on a more regular basis although this may become a feature of our altering climate; its more that we have become very dependent on centralised supplies in our modern lives. Our normalcy bias has us believing that this way our highly inter-dependent society is now set up is not at risk at all. We generally don’t even give it a second thought.

Assuming normalcy means that we assume there will always be a supermarket to get our food, water will always come out of the tap, and our lights will always turn on when we flip the switch.

The purpose of this article is not to suggest that we should introduce paranoia into our daily lives but perhaps we should give some thought towards how we could manage in the event of minor emergencies or disaster situations and how we can improve either our self-reliance or our local reliance. We should not assume that the government or the free market will always be able to provide for us in crisis events and believing this may be quite naive.

Through pursuing economies of scale and profit, big business has slowly been changing how our communities acquire goods and services and also who is able to provide these goods and services. Food supply is obviously an important aspect of a resilient community. Most of us are aware of how large supermarket chains squeeze small food suppliers out of existence. Thankfully in Ireland, it seems there is no shortage of small food producers who by their existence, add a high degree of resilience to our communities.

Other concepts which can help build community resilience and strengthen connections:

- Food co-ops where people buy produce in bulk and distribute it amongst members of the community who join up.

- Local currency initiatives – such as the Kilkenny “CAT” which was proposed in 2010 but doesn’t seem to have happened or the thriving local versions in some UK cities like the Bristol Pound and Liverpool Pounds, which serve to encourage money circulation within local enterprises and communities.

- Lending libraries are a relatively new concept in Ireland and have started in Dublin: the same concept as book libraries only for other household items such as tools, garden equipment etc. The kind of things many of us only need occasionally and so can be better shared rather than owned with little use.

- Well attended farmers markets which incentivise local producers to meet local needs.

- LETS or Local Exchange Trading Systems which relies on credits and not currency to exchange skills and resources. This bartering system allows for people to trade skills and provides a useful outlet for people with skills to trade for other needs. Cork has such a system set up: Cork LETS Network

Another thought we had when we lost our power for a day was: for people who like to figure things out for themselves, how much of the wealth of online knowledge do we actually retain so that it might be of use to us if the electricity supply failed for a significant period of time. The WeMakeDo family love to try fixing things making use of the wealth of online guides and resources now available, but one wonders how much of that knowledge do we retain? With no power (and no internet) one wonders if one could figure out how to make, for example, a manual well pump to get a supply of water?

It’s not likely that our lives would ever depend on figuring this out, but it’s food for thought.